The 30-Second Conversation That Changed How I See Myself

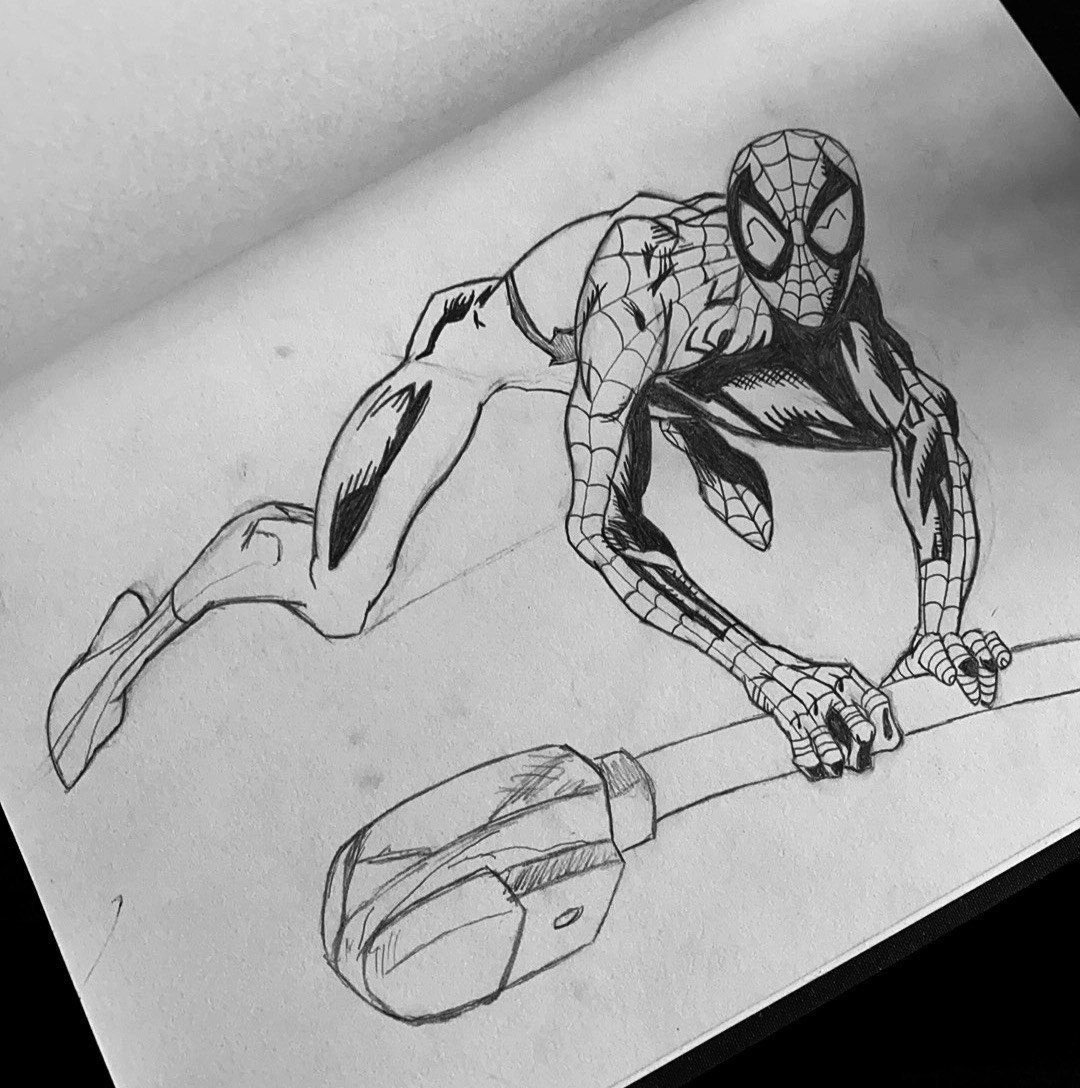

I started drawing earlier than I can remember, spending endless hours with a pencil in hand, recreating my favorite comic book characters. Whether it was perfecting Spider-Man's intricate web patterns or redrawing The Punisher's arsenal with tactical precision, I loved getting lost in the details. Each comic taught me different styles and techniques through imitation. My friends and family would marvel at my drawings, fascinated at the way I could recreate what I saw. It made me feel special. But I didn’t keep coming back to the blank page because of that feeling. I kept coming back because something inside of me yearned to be let out. It’s a feeling that is hard to describe. The intense desire to release your creativity.

Art was my thing. It was my personal escape from reality.

School was a different canvas entirely. I wasn't a great student—more like an average student who teachers said had "above-average potential." That phrase followed me throughout my high-school years. The truth was, most subjects simply didn't capture my interest. I mastered the art of doing just enough to get by, though sometimes even that strategy left me scrambling at the end of marking periods to pull my grades up.

The only exceptions were, Art Class and Woodshop. These weren't just classes—they were spaces where I could breathe, where my creativity had room to expand beyond the confines of standardized tests.

Math was my biggest struggle. While I managed to maintain passing grades in other subjects, math felt like trying to speak a language my brain refused to learn. The formulas, the single correct answers, the step-by-step processes—all of it felt foreign to how my mind naturally worked.

Then came the conversation that shifted everything.

One afternoon, I stayed after school to work on an art project in Mrs. Burns' classroom. She was my middle school art teacher and, without question, my favorite teacher. She had this way of nurturing creativity while giving students the freedom to explore beyond assignments. We started talking about my struggles in math, and I was prepared for the usual teacher advice about studying harder or getting a tutor.

Instead, she said something that stuck with me through all my remaining school years, and truthfully, my whole life:

"CJ, do you know that some of the greatest artists in history weren't good at math?"

I stopped drawing and looked up at her.

"Math is black and white," she explained. "There's only one answer to a math problem. Artists sometimes struggle with math because they're creative—it's hard for them to turn off their creativity and focus on finding that one answer when they naturally see multiple possibilities."

Then she said:

“So stop beating yourself up about math. You're not supposed to think in straight lines—that's not how artists see the world. The same mind that struggles with one right answer is the one that can see a hundred different ways to draw a tree. That's not a weakness, that's a gift.”

In that moment, an unbelievable weight was lifted off my shoulders. Something fundamental shifted in how I saw myself. My struggle with math wasn't a character flaw or a sign of lesser intelligence. It was simply a different way of thinking—one that served me well in other areas of my life.

Mrs. Burns hadn't just given me permission to struggle with math; she'd reframed my entire self-narrative. Where I had seen weakness, she showed me it was the flip side of my strength. The same mind that struggled to accept single answers was the one that could envision countless ways to capture light and shadow on paper.

Years later, as a senior in high school, I had the chance to give back through our Social Lab program, which allowed students to pursue internships during school hours. Without hesitation, I chose to return to Mrs. Burns' classroom as an assistant art teacher.

Working with her again, but from this new perspective, was deeply fulfilling. I loved helping students discover their own creative voices, but I found particular purpose in working with those who insisted they "couldn't do art." I recognized their self-doubt because I'd felt it in math class.

I'd sit with these students and share what art had taught me: that it's not something that can be truly graded or judged by conventional standards. Art can be deeply personal—a way to express what words can't capture. It can be therapeutic, offering relief from daily stresses. Or it can simply be fun, a chance to play with colors and shapes without any pressure to be "good" at it.

What I tried to pass on was what Mrs. Burns had given me: the understanding that our perceived weaknesses might just be strengths viewed through the wrong lens. That student who couldn't draw a realistic portrait might create abstract pieces that conveyed emotion in ways realism never could. The one who struggled with perspective might excel at pattern and design.

The lesson I carry from those experiences is this: Sometimes the biggest obstacles we face aren't external—they're the stories we tell ourselves about our limitations. Real growth happens when we stop trying to force ourselves into boxes that don't fit and instead embrace the unique shape of our own capabilities.

Mrs. Burns taught me that being "bad at math" wasn't a verdict on my intelligence or potential. It was simply information about how my mind preferred to work. Once I understood that, I stopped wasting energy feeling inadequate and started investing it in developing my actual strengths.

The path forward isn't always about fixing what we think is wrong with us. Sometimes it's about recognizing that what we've been calling weaknesses might actually be the foundation of our greatest strengths. The key is changing the story we tell ourselves—dismantling those mental cages we've built from others' expectations and our own limiting beliefs.

Here's what I know now that I couldn't see then:

Every time you've been told you're not living up to your potential, every time you've felt stupid because your brain works differently, every time you've believed you're somehow less than—you've been accepting someone else's definition of who you should be.

But those definitions? They're just pencil marks.

You're the artist.

The most powerful thing Mrs. Burns taught me wasn't about math or art. It was that the story I'd been telling myself—that I was struggling because I couldn't think in straight lines—was just that: a story. And stories can be rewritten.

So pick up your pencil. Cross out the words that were never yours to begin with. Draw outside every line they give you. Because the moment you realize you're the author of your own story is the moment you stop being trapped by it.

The cage was never locked. You were just told it was.

Run the hills.

Chas